|

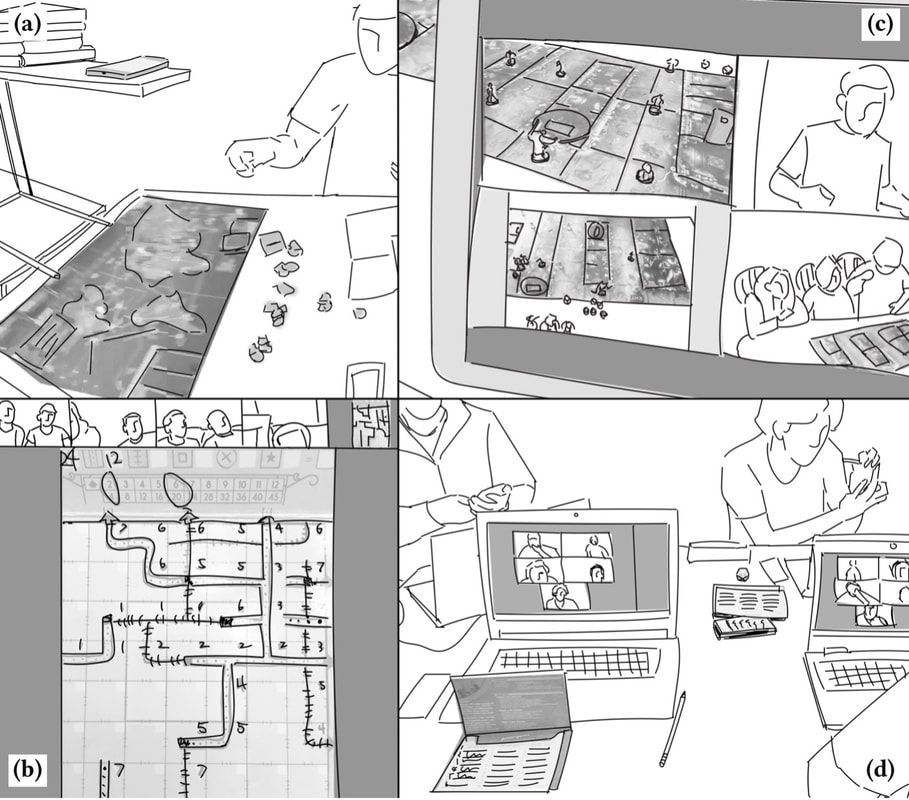

Irene Ye Yuan (UMN, department of computer science) and I, along with Ruotong Wang and Svetlana Yarosh, wrote this paper last year during quarantine for CHI 2021, which was scheduled to be held this May in Yokohama. (Not gonna happen.) Although we can't physically be there to eat the ramen and shumai, we decide to write a blog post about this paper to celebrate the one thing we gained from COVID-19: unexpected remote collaboration. For those who don't know: CHI – pronounced ‘kai’ – is generally considered the most prestigious in the field of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and attracts thousands of international attendees annually. We also received honorary mention for this paper! Pretty cool, ain't it? Tabletop Games in the Age of Remote Collaboration: Design Opportunities for a Socially Connected Game Experience Now that you are (almost) vaccinated, do you remember this time last year when you had been stuck at home for two months and was aching for some human interaction? How long have you been fantasizing your next game night? Did you wonder, how did other board-game enthusiasts cope with COVID-19? Curious about how people appropriate existing technologies to play tabletop games online and the socio-technical factors that affected people’s gaming and social experiences, we interviewed 15 players to look for some answers. (We also spent a lot of time scraping and reading posts and comments on Reddit, Twitter, and Instagram.) And by doing so, we identified three themes that best describe people’s social and game experiences: Figure 1. Traced pictures of examples for Hybrid Setups retrieved from online observation: (a) Gamemaster does-it-all (board view); (b) Gamemaster does-it-all (videochat view); (c) mirrored board (videochat view); (d) pen-and-paper. 1. Shared space. Physical board, rolling dice, or deck of cards, while being a vital part of the offline experience, also create a sense of togetherness in the same game space, and many players feel inclined to recreate this space virtually by utilizing the hybrid setup. One example of the hybrid setup is what we call “gamemaster does-it-all,” in which the gamemaster sets up a physical board and manipulates the components while sharing the board via a mounted smartphone with other players.

2. Shared Information and Awareness. In offline games, information is communicated not only verbally, but also through indirect non-verbal social cues such as body gestures and eye contact. To make up for the lack of shared information, players tend to communicate via multiple channels simultaneously, including video, audio, and text messages. 3. Shared Time. When tabletop games move online, the structure of time in these remote game sessions changes. Game sessions become easier to schedule online versus in-person, but because of screen fatigue and the lack of social cues, these sessions tend to be shorter. Obviously, not all of these make-shift appropriations of existing technologies work perfectly. For example, the lack of non-verbal cues such as eye contact is likely to make players feel disconnected. One interviewer said that when his eight-year-old son played chess online with a friend, moving out of the camera area could frustrate the other player, since they couldn’t tell whether their opponent was still engaging in the game. Plus, the hybrid setup makes it a lot harder to be a gamemaster: not only do they have to throw the dice and move the chips for everyone, they are also responsible for memorizing different players’ states in the game. One participant said that his remote game experience feels “almost like work,” and he was acting like “a human computer.” But there are also some pleasant surprises. “Sharing time” remotely does not require all players to be present in the same space, which makes it much easier to schedule a game while accommodating the needs of people from different time zones and under different work or parenting schedules. “Shared information” might be harder to acquire during remote play, but players came up with creative ways to cope with the lack of social and non-verbal cues, such as one-on-one texting during a group game, using audio-only chat to allow for more space for imagination during TRPG games, or manipulating game rules to create a better social experience. Even glitches can be enjoyable: one participant discussed how certain unintended mechanisms in the game she played with her family helped to balance the competitiveness between players by periodically reset the player’s score back to zero once a browser advertisement pops out. These findings help us identify a number of design opportunities to better support social connections during remote collaborative play. While current online tabletop game platforms tend to focus on rule enforcing, we find that allowing players to customize rules, scoring system, and teaming strategies could potentially make the social experience better. A system using a camera to sense and communicate head and face directions, eye gaze, and heart rate could help build awareness during a remote game session. Incorporating more augmented physical components in a hybrid setup could help, too.

106 Comments

|

ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed