|

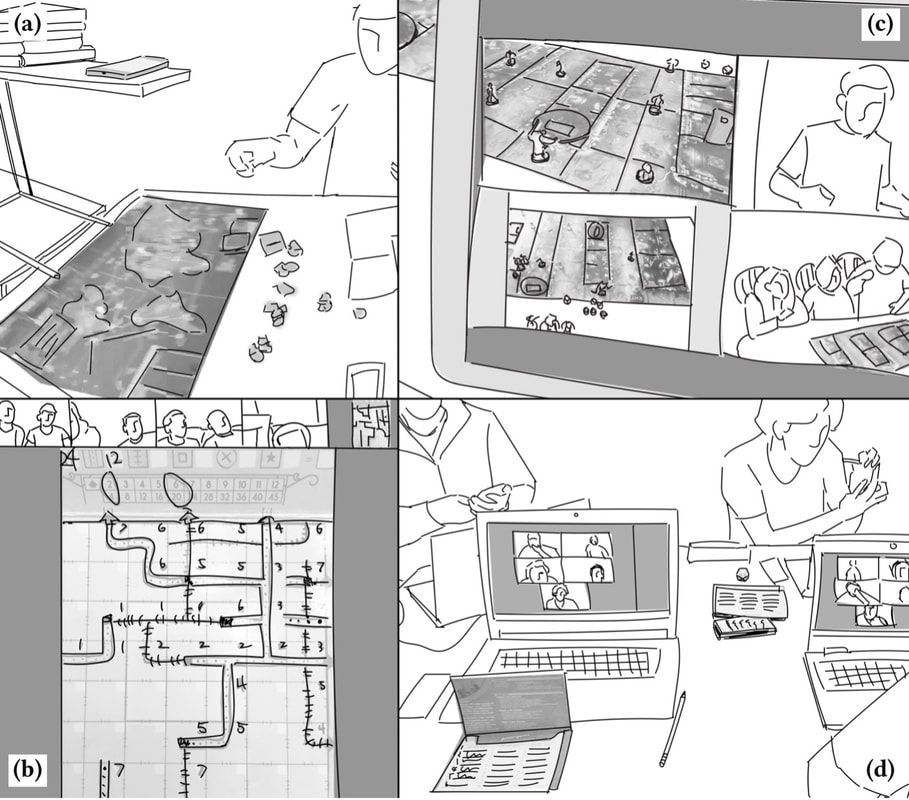

Irene Ye Yuan (UMN, department of computer science) and I, along with Ruotong Wang and Svetlana Yarosh, wrote this paper last year during quarantine for CHI 2021, which was scheduled to be held this May in Yokohama. (Not gonna happen.) Although we can't physically be there to eat the ramen and shumai, we decide to write a blog post about this paper to celebrate the one thing we gained from COVID-19: unexpected remote collaboration. For those who don't know: CHI – pronounced ‘kai’ – is generally considered the most prestigious in the field of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and attracts thousands of international attendees annually. We also received honorary mention for this paper! Pretty cool, ain't it? Tabletop Games in the Age of Remote Collaboration: Design Opportunities for a Socially Connected Game Experience Now that you are (almost) vaccinated, do you remember this time last year when you had been stuck at home for two months and was aching for some human interaction? How long have you been fantasizing your next game night? Did you wonder, how did other board-game enthusiasts cope with COVID-19? Curious about how people appropriate existing technologies to play tabletop games online and the socio-technical factors that affected people’s gaming and social experiences, we interviewed 15 players to look for some answers. (We also spent a lot of time scraping and reading posts and comments on Reddit, Twitter, and Instagram.) And by doing so, we identified three themes that best describe people’s social and game experiences: Figure 1. Traced pictures of examples for Hybrid Setups retrieved from online observation: (a) Gamemaster does-it-all (board view); (b) Gamemaster does-it-all (videochat view); (c) mirrored board (videochat view); (d) pen-and-paper. 1. Shared space. Physical board, rolling dice, or deck of cards, while being a vital part of the offline experience, also create a sense of togetherness in the same game space, and many players feel inclined to recreate this space virtually by utilizing the hybrid setup. One example of the hybrid setup is what we call “gamemaster does-it-all,” in which the gamemaster sets up a physical board and manipulates the components while sharing the board via a mounted smartphone with other players.

2. Shared Information and Awareness. In offline games, information is communicated not only verbally, but also through indirect non-verbal social cues such as body gestures and eye contact. To make up for the lack of shared information, players tend to communicate via multiple channels simultaneously, including video, audio, and text messages. 3. Shared Time. When tabletop games move online, the structure of time in these remote game sessions changes. Game sessions become easier to schedule online versus in-person, but because of screen fatigue and the lack of social cues, these sessions tend to be shorter. Obviously, not all of these make-shift appropriations of existing technologies work perfectly. For example, the lack of non-verbal cues such as eye contact is likely to make players feel disconnected. One interviewer said that when his eight-year-old son played chess online with a friend, moving out of the camera area could frustrate the other player, since they couldn’t tell whether their opponent was still engaging in the game. Plus, the hybrid setup makes it a lot harder to be a gamemaster: not only do they have to throw the dice and move the chips for everyone, they are also responsible for memorizing different players’ states in the game. One participant said that his remote game experience feels “almost like work,” and he was acting like “a human computer.” But there are also some pleasant surprises. “Sharing time” remotely does not require all players to be present in the same space, which makes it much easier to schedule a game while accommodating the needs of people from different time zones and under different work or parenting schedules. “Shared information” might be harder to acquire during remote play, but players came up with creative ways to cope with the lack of social and non-verbal cues, such as one-on-one texting during a group game, using audio-only chat to allow for more space for imagination during TRPG games, or manipulating game rules to create a better social experience. Even glitches can be enjoyable: one participant discussed how certain unintended mechanisms in the game she played with her family helped to balance the competitiveness between players by periodically reset the player’s score back to zero once a browser advertisement pops out. These findings help us identify a number of design opportunities to better support social connections during remote collaborative play. While current online tabletop game platforms tend to focus on rule enforcing, we find that allowing players to customize rules, scoring system, and teaming strategies could potentially make the social experience better. A system using a camera to sense and communicate head and face directions, eye gaze, and heart rate could help build awareness during a remote game session. Incorporating more augmented physical components in a hybrid setup could help, too.

106 Comments

In Yoko Tawada’s post-apocalyptical novel The Emissary (献灯使), a massive irreparable disaster (hinting at the 3.11 East Japan earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster) results in serious environmental consequences to which the stronger-than-ever elderly and children with feeble bodies must learn to adapt: radioactive soil, dangerous water, extinction of animal and plant species, privatized government and police force, and so forth. In this world, eating becomes incredibly dangerous. The main character Mumei, a child so weak that he can barely walks, has serious allergic reactions to most of the food he takes in: “When Mumei ate kiwi fruit he had trouble breathing; lemon juice paralyzed his tongue. And it wasn’t just fruit. Spinach gave him heartburn, while shiitake mushroom made him dizzy. Mumei never forgot for an instant that food was dangerous.”

As ridiculous as it sounds, the world we live in is gradually becoming one that resembles that of Mumei. Think about it: when was the last time you ate an apple bought from the store without religiously washing both your hands and the apple for a good 30 seconds? I have seen videos and images of grandmothers soaking the entirety of their grocery delivery in the bathtub in water (if not some suspicious cleaning product). I worry about cooks/servers coughing at my freshly deep-fried chicken fingers. My body does not automatically react to the danger in the same way Mumei does—kiwi fruit does not give me trouble breathing—but I feel the danger nevertheless. Rather than feeling sorry for himself, Mumei deals with the pain by finding new ways of eating it, or, as his great-grandfather Yoshiro calls, “playing with food.” The older generation believed that standardizing the eating process into a ritual could sooth their cells into ignoring the sourness of an orange or a grapefruit, which actually warned of danger. Mumei’s generation, however, would never be deceived by tricks like these, because no matter how they eat fruits, they will always feel the pain. I was reminded by this episode of Mumei playing with orange as I re-read Ian Bogost’s Play Anything, when he tells the story of his young daughter playing “step on a crack” as she was being dragged around the mall. And Bogost’s analysis is, children play even when they have no control over the situation, because unlike adults, they are less inhibited, less powerful, much smaller, and often forced into situations that are not designed with their desires and welfare in mind. “Misery gives way to fun when you take an object, event, situation, or scenario that wasn’t designed for you, that isn’t invested in you, that isn’t concerned in the slightest for your experience of it, and then treat it as if it were…Play isn’t doing what we want, but doing what we can with the materials we find along the way. And fun isn’t the experience of pleasure, but the outcome of tinkering with a small part of the world in a surprising way.” The idea that misery gives way to fun is paradoxical. Bogost provides examples of frustrating video games and iambic pentameter in poetry that create artificial limit that turn out to be fun in an experience. But things could be a little more subversive than that. Children turning the miserable experience of being schlepped around into a game is challenging the ways in which things in the adult world work, turning serious stuff into something lighthearted and funny. Mumei poking at his orange is disassociating pain with meanings such as punishment and abuse, and turning it into something neutral and indifferent. Mumei is only playing with his food; he is also playing with danger and pain. How do we play in a dangerous world when things no longer make sense, when objects that we once so carefully designed to work just for us suddenly turn against us? During the COVID-19 pandemic, our trusted door handle and elevator button suddenly become the source of fear. The meaning of things changed overnight, from the shortcut that takes us to places to a dangerous surface covered with gems. A friend of mine posted on Facebook that she was watching The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel the other night, and all she could think about is how close people are standing next to each other, hugging and kissing and failing to follow the order of social distancing. The rules of our game is now changed: the courtesy rule that requires all the bisous and hugs and handshakes is now replaced by the order of social distancing that instructs us to stand 2 meters apart in the supermarket check-out line. It is as if us adults are suddenly thrown in the world of children, where we are surrounded by sharp objects and furnitures that are too high for us. When I was a child, I always confirm with my mom, “can I eat this?” before putting anything in my mouth. I’m feeling that anxiety all over again as I unconsciously ask myself the same question before putting anything in my mouth: would this kill me? But (a reasonable amount of) anxiety and limitations could also be “fun,” since the rigid rules of the adult world no longer apply to those of us fortunate enough to be able to “work” from home: now we all get up way too late and wear pajamas to work. The Internet is spotty. Dogs bark in the background. Everything suddenly becomes extremely ad hoc! It’s our chance to play now! (Disclaimer: I’m not saying COVID-19 is “fun.” It is a highly unpredictable and extremely contagious virus, and I’ve been closely monitoring its development since early January, since I was extremely concerned for my parents—my mom is an ICU doctor in China, and my dad belongs to the high risk group. I even talked about the virus in my job talk in mid February. It’s been three months, I’ve received countless emails of rejection and indefinitely postponed searches, and I’m tired. I hereby give permission to myself to have a little bit of fun.) In the past week, I have been playing the Animal Crossing: New Horizon game every day. The game is laid-back: land on an island and collect fish, bugs, and fruits and sell them for bell currency to buy furniture and other decorative nonsense for your island. You invite funny little animals to join you on the island (I got randomly assigned two gorillas!). That’s it. It is arguably a system that resembles 17th century Japanese feudalism/ capitalism at its early stage, as you take on a loan for your house, and that loan grows bigger and bigger as your desire expands. But you don’t have to do that. The game is extremely low stress—there’s no punishment if you don’t pay back the loan. Everything is fine, except you get a pile of rotten radish if you “time-travel” by setting the time of your hardware back and forth, but even the spoiled radish attracts new insects for you to collect). Tonight some of my friends decided to do a little “night market” on my island. In the game, once you have touched one item, the item will be catalogued in your ATM terminal and can be purchased later. We then decided to come together, drop our items on the ground, and touch each other’s stuff. It’s so dumb that we loved it. Then we watched a meteor shower together while hitting on each other’s head with a butterfly net. I’ve been following the #ACNH hashtag on twitter, and every day I see other people posting silly videos of racing with each other in a maze, playing hide and seek, or chopping down trees to play music chair. Poets (and philosophers) tend to take themselves rather seriously and ask questions like ”wozu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit?” (What are poets for in a destitute time?) But games—particularly those that are not goal-oriented, such as hitting each others’ head with a butterfly net— do not require those “wozu” kind of question. And the meaninglessness is kinda the point: it makes fun of principles, standards, meanings ,and whatever else the adult world forces us to believe. Art and poetry ask those “wozu” questions because they attempt to find new meanings that are not there yet, but games, they make sure that nobody takes “meanings” seriously in the little world it creates. And that’s perhaps why we need games in a destitute time. No matter how much fun we have in ANCH, we still need to get out of the bed tomorrow morning and dress like a sane person for the next Zoom meeting. But games teach us that norms and regulations are nothing more than ad hoc rules one invented in a game. When the time comes, things break apart, rules no longer apply, and we must start all over again like a child trying to find her way through the mall. Playing in a destitute time is to wrap one’s mind around the new norms and confront new problems head-on. Playing in a destitute time is to stop pretending that everything will return to normal and be fine, and to find new ways to deal with the inescapable pain that is going to happen. Mumei plays with orange because he has to eat it. Relying on rituals or standardized process is the older generation’s way of self-deception. It doesn’t work any more. This is my way of justifying way too many hours in ANCH in the past week. It was necessary. Now if you would excuse me, I’m gonna go jump over holes to try to catch a tarantula. |

ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed